Bill 184: Wrong Bill, Wrong Time

Update

While not surprised, the Advocacy Centre for Tenants Ontario (ACTO) is disappointed with the passing of Bill 184, Protecting Tenants and Strengthening Community Housing Act, 2020. It received Royal Assent yesterday and its amendments to the Residential Tenancies Act, 2006 (RTA) are now in effect. The Bill was pushed through the legislative process, without meaningful consultation or consideration of the concerns raised by tenants, at a time when the health and livelihoods of tenants have been hit hard by the pandemic crisis.

Contrary to its title, Bill 184’s amendments to the RTA will not protect tenants from bad faith evictions and will make it easier for landlords to evict tenants without a hearing. It will also limit tenant’s ability to raise defences at arrear hearings and subject former tenants to hearings at the Board without proper service of legal documents. These changes will exacerbate the ongoing affordable housing crisis and make tenants more vulnerable to evictions and homelessness.

The pandemic crisis has revealed the extent of the affordable housing crisis in cities across the province. The affordable housing shortage is a public health crisis we can no longer ignore. We know that difficult times lie ahead for the majority of tenants living on lower incomes in this province. We will continue to push for the protections that tenants need to access safe, secure and affordable homes.

Original Campaign – Tell Ontario to Scrap Bill 184

Low to moderate income tenants in Ontario face daily struggles to pay the rent and life’s other expenses. This is because rents in this province have been on a constant rise. Many tenants will point out the state of disrepair in their homes while paying exorbitant monthly rents. Rising rents are the result of laws that put landlords’ interests first, including the right of landlords to rent gouge on tenant turnover.

The COVID-19 pandemic crisis has laid bare the growing gap between the haves and the have-nots, made worse by these policies. Yet, in the middle of the crisis, the Ontario government has decided to push through Bill 184, Protecting Tenants and Strengthening Communities Housing Act – a collection of pro-landlord amendments that will impoverish and displace tenants.

The only tenant protection in Bill 184 is in the title. This Bill is out of touch with the challenges faced by tenants, especially as the pandemic crisis has deepened their vulnerabilities.

Many organizations have signed an open letter, Bill 184: Wrong Bill, Wrong Time, voicing their deep concerns with Bill 184.

We urged the government to scrap the Bill and instead take the following actions:

1. Update the purpose of the Residential Tenancies Act (RTA) to include improving public health in Ontario and recognizing the progressive realization of the human right to housing as enshrined in the federal legislation.

2. Extend the current eviction moratorium until the pandemic and the post-pandemic recovery period are over to ensure enough time for employment rates and other economic indicators to return to pre-COVID-19 levels. While urgent matters with serious health and safety implications continue to be heard, Ontario must commit to keeping people housed.

3. Amend the RTA to provide direction to the Landlord and Tenant Board (LTB) for mediated repayment agreements that are feasible and will not push tenants into homelessness or continued poverty.

4. Provide the LTB with direction on providing relief from eviction due to circumstances caused by the pandemic crisis. Good tenants that lost their employment, faced illness or had to take care of their children out of school should not be punished because they faced financial hardship during this pandemic.

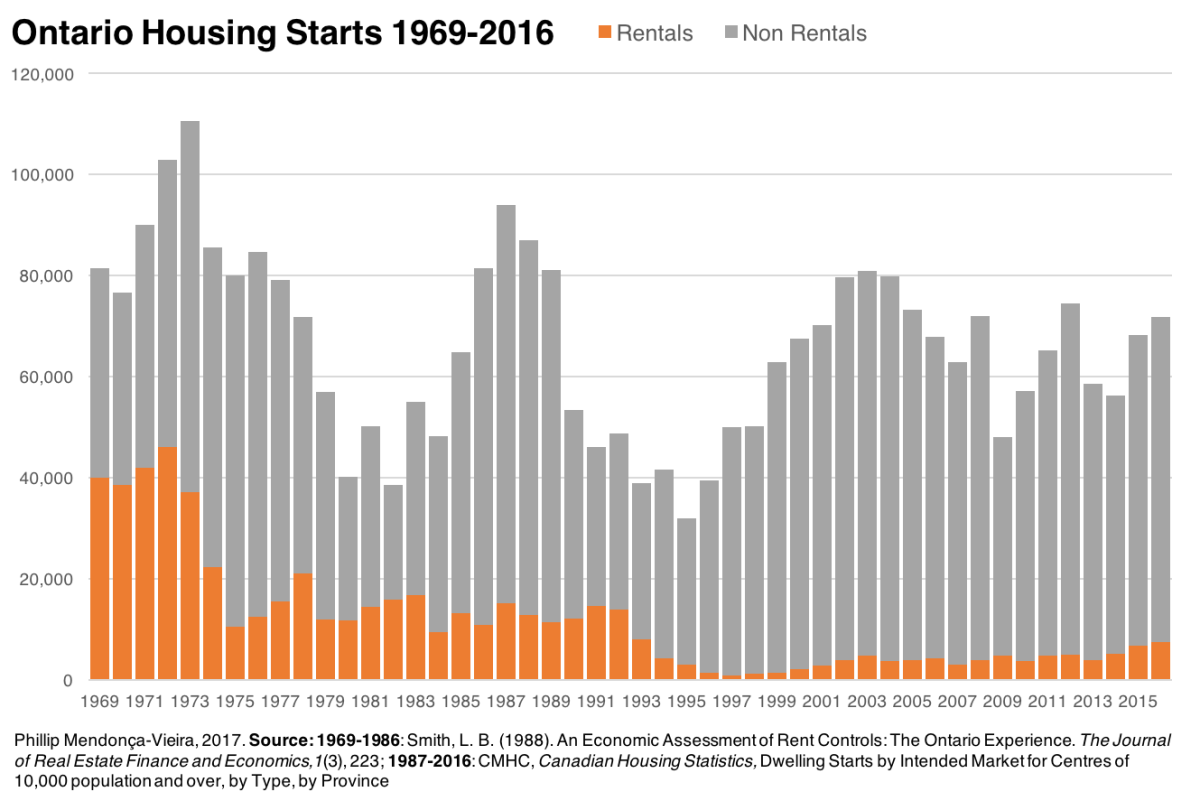

5. Re-institute effective rent control and alleviate the greatest source of anxiety for tenants even before this pandemic crisis – the unaffordable rents that skyrocket every year, displacing people from their homes and communities.

If you agree with these recommendations, send an email to Ontario’s

Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing to show your support.